What do you see in the photo, above? What do you see in the photo to the

right? Now, think about each of those photos. Is what you think you’re

seeing actually what’s going on in that picture, or might you have drawn a

conclusion, ahead of time, about what you thought you should be seeing

in each case? For example, how many flowers do you see in the photo, above?

In science, it’s important to train your mind to draw conclusions based on

what you see, rather than seeing based on an assumption/conclusion.

What do you see in the photo, above? What do you see in the photo to the

right? Now, think about each of those photos. Is what you think you’re

seeing actually what’s going on in that picture, or might you have drawn a

conclusion, ahead of time, about what you thought you should be seeing

in each case? For example, how many flowers do you see in the photo, above?

In science, it’s important to train your mind to draw conclusions based on

what you see, rather than seeing based on an assumption/conclusion.

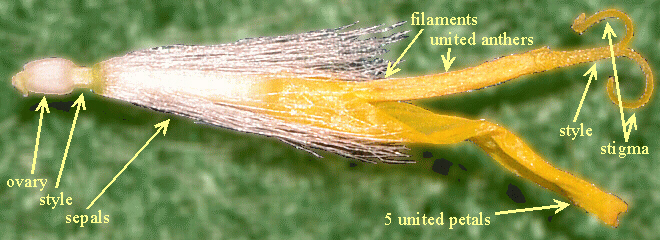

Here’s a close-up of the left-hand edge of the top photo. Notice that each

of what appears to be a “petal” has five small tips on it. It turns out that

each of those tips is, in fact, the tip of a petal, and those five

petals of that one flower are united such that at their base they

form a short tube which, then, expands into the flat part that you see.

Here’s a close-up of the left-hand edge of the top photo. Notice that each

of what appears to be a “petal” has five small tips on it. It turns out that

each of those tips is, in fact, the tip of a petal, and those five

petals of that one flower are united such that at their base they

form a short tube which, then, expands into the flat part that you see.

Also, in the top photo, notice that the curly reproductive

parts arise from “all over,” and not just in the center. In fact, each of

those reproductive structures arises from its own flower, each of

which is surrounded by its own set of five petals as just described. Here’s

a close up of one of the individual flowers. The dandelion at the top of

this page is, then, actually a head made up of a whole bunch of small

flowers (sometimes referred to as “florets”) all grouped together.

Here’s a photo of a head, a group of flowers, from a closely-related plant.

Can you distinguish the individual flowers and their five petals?

Here’s a photo of a head, a group of flowers, from a closely-related plant.

Can you distinguish the individual flowers and their five petals?

What about the second picture, above? Other than a really

raunchy banana slice sitting in a blue dish, there’s obviously “something”

on the banana. It looks sort-of like a dead leaf, but it’s upright. It

looks sort-of like some kind of bird with its head/beak on the upper left,

but there’s no eye on what appears to be its head. Also, there’s nothing

under it that looks like bird-type feet. . . but if you look/observe very

carefully under it, you may spot five, “thread-like things” sticking out:

two straight ones that are somewhat parallel going to the right, one crooked

one coming out towards us,

and two that are bent in the middle and are sort-of going to the left. In

the middle, there’s a yellowish spot that looks kind of like it might be a

hole in the leaf, but it also reminds me of similar-looking spots I’ve seen

on the wings of various kinds of moths and butterflies. Also, I think I see

a line running from the notch along the top edge, down to the middle bottom

that resembles the front edge of the hindwing of a butterfly. Come to think

of it, the bent “thread-like things” to the left and under it do look rather

like butterfly legs and the straight ones on the right do look like antennae.

Based on my observations, I’m going to draw the tentative

conclusion that this appears to be a Dead Leaf Butterfly with its head

on the lower right and its “back end” raised up on the left side (perhaps I

could go online and look for other Dead Leaf Butterfly photos with which to

compare this one). Too bad this is only a photograph — if you had been there

with me at Callaway Gardens in Pine Mountain, GA when I took this photo, you

might have been able to get a closer look from several directions and see if

it moved or just stayed there.

|

|

Recently, I saw this plant for sale in the house-plant section

of a local hardware store, and immediately, the unusual leaf venation caught

my attention. I remembered that years ago, I once had ordered a tree sapling

from an exotic plant nursery, and it had the same, unusual leaf venation.

That led me to the hypothesis that perhaps this was the same kind of tree.

I looked at

the tag, but all it said was that this was a house plant. I asked an employee,

but he didn’t know what it was. It turns out that right then, there was also

an employee from the plant grower/supplier there, too, and she didn’t know

what it was, either. I mentioned to the store employee what I thought it

might be, he found an inconspicuous, “safe” place and gently scratched

the bark with his fingernail, and we both smelled it. So, observation #2:

the bark smelled like cinnamon. Thus, when the tree and I got home, I did

a Google search, looked at some other photos online, and read what Wikipedia

and several other Web sites had to say. Based on all those observations, I

came to the conclusion that, indeed, this tree is a cinnamon tree (although

I’m not sure exactly which of several, closely-related species).

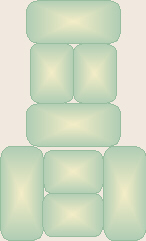

A common sight in autumn in this part of the country is Osage Orange fruits

scattered on the roadside. Several years ago, as I was staring at one of

these, I realized there is a very precise pattern to the way in which the

“bumps” are organized on an Osage Orange fruit. In chemistry, you may have

learned about closest packing of spheres, where each atom usually

has six nearest neighbors, and that “rule” also holds true for the cells in

our tissues, but Osage Orange fruit is organized quite differently.

A common sight in autumn in this part of the country is Osage Orange fruits

scattered on the roadside. Several years ago, as I was staring at one of

these, I realized there is a very precise pattern to the way in which the

“bumps” are organized on an Osage Orange fruit. In chemistry, you may have

learned about closest packing of spheres, where each atom usually

has six nearest neighbors, and that “rule” also holds true for the cells in

our tissues, but Osage Orange fruit is organized quite differently.

The “bumps” on an Osage Orange fruit are organized in sets of four, with two

in the middle, and one on each end of a group. Adjacent groups are often

oriented at right angles to each other.

So often in scientific investigation, the small, seemingly

insignificant details end up being the most important key to the problem at

hand. Yet, because of the culture in which we live and/or because of our

unfamiliarity with a field, we do not notice these things. Often, too, we

misinterpret what we see, mistaking conclusions for observations, and thus,

come to a wrong conclusion overall.

For example, if I observe an ant carrying a seed, it is

just that. Unless I actually see that ant or its nestmates eating that seed,

I cannot say that the ant is carrying a piece of food. Perhaps that seed is

merely in the way and being removed, perhaps it will serve as a substrate

upon which the ants will grow fungus to eat, or perhaps it will serve some

other function. Thus, if I make the “observation” that the ant is carrying a

piece of food, it might lead me to a false conclusion later on that, for

example, the anthill is being invaded by an unwanted fungus. As another

example, “The ants are under the apple slice,” is an observation, but “The

ants are hiding under the apple slice,” or “The ants are looking for food

under the apple slice” are both making unsubstantiated assumptions or drawing

conclusions about the ants’ behavior or their relationship to the apple.

(In Dr. Fankhauser’s photo, these ants were headed into the dog’s food dish.)

For example, if I observe an ant carrying a seed, it is

just that. Unless I actually see that ant or its nestmates eating that seed,

I cannot say that the ant is carrying a piece of food. Perhaps that seed is

merely in the way and being removed, perhaps it will serve as a substrate

upon which the ants will grow fungus to eat, or perhaps it will serve some

other function. Thus, if I make the “observation” that the ant is carrying a

piece of food, it might lead me to a false conclusion later on that, for

example, the anthill is being invaded by an unwanted fungus. As another

example, “The ants are under the apple slice,” is an observation, but “The

ants are hiding under the apple slice,” or “The ants are looking for food

under the apple slice” are both making unsubstantiated assumptions or drawing

conclusions about the ants’ behavior or their relationship to the apple.

(In Dr. Fankhauser’s photo, these ants were headed into the dog’s food dish.)

Also, it is amazing how frequently or how long we can look at

something and never see that which is perfectly obvious about it. This is

the basis of many of our optical illusions. As biologists in a three-dimensional

world of living organisms, we have the opportunity to use our senses of touch,

hearing, and chemoreception to aid our sense of sight, yet we frequently use

only what we see.

This lab may be done outdoors (weather permitting), or indoors

if the weather is rainy. Outdoors, there are many living organisms from trees

to smaller plants, insects, birds, etc. Indoors, there are a number of plants

in the greenhouse and out in the hallway. There may also be insects or

spiders in the greenhouse, or perhaps some other animals to be seen.

Pick one of these many organisms, (ant colony, tree, beetle, wildflower, bird,

etc.) and list in your lab notebook at least twenty (20) things you

observe about it. Record descriptive things like its smell, its

sound, how it feels (texture), what it looks like – shape, color,

etc., etc. Be specific on size (how many centimeters?), and don’t just say

it’s “big” or it’ “small” (relative to a blue whale, an elephant is tiny, and

relative to an eyelash mite, an ant is huge).

Don’t worry if you don’t know what this organism is called – actually,

knowing what it is might bias you and tempt you to make conclusions instead

– but do think about what traits/characteristics of that organism might be

distinguishing features you could potentially use to identify it (How many

legs does it have? How are its leaves arranged?). Be careful you do not

include any conclusions among your observations. You may find that the first

two or three observations are “easy” and then it gets harder to think of

things – that’s normal. Just sit there and think a while, and often, a

number of new observations will suddenly come to you. Drawing a picture of

your organism would probably help you to “see” it better, providing you

really look at it to see how to draw it and not just think, “I can’t draw,”

and make only a quick sketch. Especially with plants, remember to observe

the whole organism not just a portion of it. For plants in the greenhouse,

the fact that the plant is in a pot (as opposed to the ground) and the size

of the pot relative to the size of the plant may be “significant”

observations that relate to the plant, but things such as the color and shape

of the pot are observations of the pot, not the plant, and as such,

would most-likely be totally irrelevant to the plant, itself.

Make sure you have all of the following in your lab notebook: