Earthworm Anatomy

Background — Phylum Annelida:

(annel = a little ring, a ring)

Annelid classes include

- Class Oligochaeta (oligo = few, scant; chaeta, setum

= bristle), earthworms with few setae;

- Class Polychaeta (poly = many), marine worms with

projections from each segment (parapods — para = beside,

near; poda = foot) which serve as gills and bear many setae;

- Class Hirudinea, leeches.

Annelids are segmented, both inside and out. They have a

tube-within-a-tube body plan, a closed circulatory system with five pairs of

“hearts,” and a ventral, solid, nervous system which arises from mesoderm

tissue. (Compare this with the vertebrate nervous system which is dorsal,

hollow, and of ectodermal origin.). Many of the internal organs, for

example, the paired nephridia (nephri = kidney) which serve an

excretory function analogous to our kidneys, are repeated in each segment.

Annelids have both longitudinal and circular muscles, so have better control

over their movement than the Nematodes (which only have longitudinal

muscles) do.

Leeches are “famous” for their diet: they suck blood. Some have sharp jaws

to slit their host’s skin, while others secrete an enzyme to digest a hole

in the victim’s skin. It is to the leech’s advantage if the would-be victim

remains unaware of the leech’s presence, thus most leeches secrete some kind

of anesthetic (an = not, without; aesthet = sensitive,

perception) so the host does not feel their attack. To prevent the blood

from clotting before they ingest it, leeches also secrete an anticoagulant

(anti = against, opposite; co- = with, together;

ageve = to move, put in motion; coagulum = rennet). For years,

people thought disease was caused by too much blood, so the Medicinal Leech

Hirudo medicinalis was used to suck some out. Typically a medicinal

leech, once attached, may suck for a couple hours, perhaps ingesting between

one to two ounces of blood, many times its own body weight. While we now

have different theories as to the cause of diseases, medicinal leeches still

have uses in modern medicine! When someone severs a finger which must be

surgically reattached, since all the capillaries are dysfunctional, blood

flowing into the finger via the reconstructed arteries has nowhere to go but

into the tissue. This leads to problems with edema in the area. Also,

because of this poor circulation, the reattached tissues cannot get the air

and nutrients they need to heal properly. It has been discovered that

letting a leech suck on the end of the reattached finger will a) help reduce

edema, and b) create a sort-of blood flow that will allow nutrients and air

to get to the reattached tissues so they heal better and more quickly.

Additionally, the anticoagulant secreted by the Medicinal Leech is very

powerful, and a leech bite (in a person whose blood usually clots normally)

can take a couple days to stop bleeding and form a scab. Research is being

done on using this powerful anticoagulant to help heart attack and stroke

victims whose problems are caused by blood clots.

Marine worms have a pair of gill-like structures called

parapods projecting from the sides of each segment. It is believed

that the early annelid ancestors of insects (and other arthropods) may have

looked like this (and the parapods later became modified into true legs).

Background — Earthworms:

In this lab, you will become familiar with the external and

internal anatomy of the earthworm, Lumbricus terrestris.

As members of Phylum Annelida, earthworms have bilateral

(bi = two, later = the side) symmetry and a “tube-within-a-tube”

body plan. A distinguishing feature of this phylum is the division of the

body into segments. This segmentation is both external and internal

with many structures/organs repeated in each segment. The body has three

tissue layers:

- ectoderm (ecto = outside, out, outer; derm =

skin)

- mesoderm (meso = middle)

- endoderm (endo = within, inner)

The coelom (coel = hollow) is a cavity between

the layers of the mesoderm. The circulatory system is a closed

circulatory system, meaning that the blood remains within the blood

vessels (in an open system, the “blood” bathes the body organs for at least

part of its journey).

Earthworms live in the soil, working their way through it to

ingest and digest organic matter within the soil. They play an important

part in aerating and fertilizing the soil.

Earthworms exchange air (“breathe”) through their moist skin,

thus if a worm dries out, besides the dangers of dehydration, it can’t get

air so it dies. However, earthworms also cannot live underwater, and if the

soil in which they are living becomes totally filled with water during a

heavy rain, they will all come to the surface so they don’t drown (and end

up on the sidewalk where they subsequently dry out after the rain stops).

Earthworms are hermaphroditic and a pair of worms fertilize

each other.

External Anatomy:

Obtain a dissecting tray (Please note that this is not a toy.

Try to avoid unnecessary pin holes in the wax and DO NOT CARVE, chop, or

otherwise mutilate the wax.) and a set of dissecting tools, as well as your

dissecting scope and its light. (Eventually, you will also need your

“regular” microscope.) Also, obtain a rinsed, preserved earthworm.

As you do your dissection, compare what you’re seeing in your worm with

the large worm model. Draw a labeled illustration of and take notes on

everything you view.

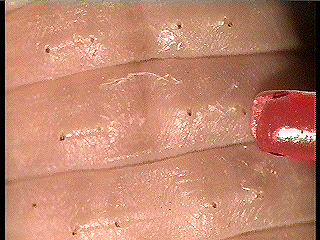

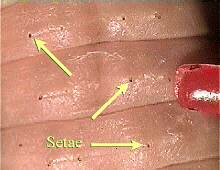

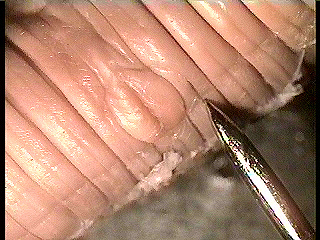

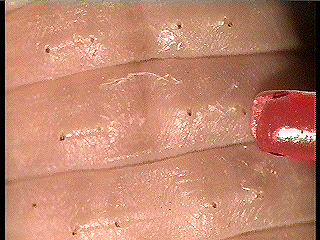

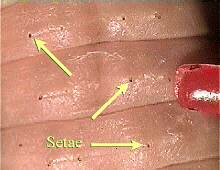

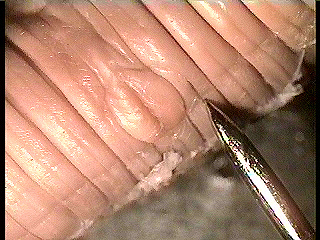

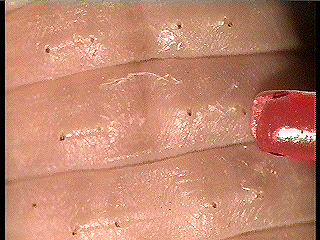

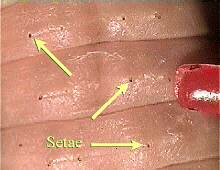

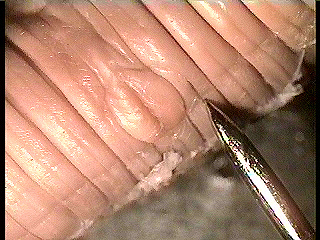

External View, Four Pairs of Setae

Labeled Setae

- Feel the bristly setae

(seta = bristle) on each segment, along the sides and bottom. Note

that there are four pairs. Two pairs are on the sides (laterally —

later = the side) and two pairs are on the bottom (ventrally

— venter = the underside, belly).

- Note the conspicuous swelling near

the anterior (the front — ante = before) end called the

clitellum (clitell = a pack saddle). The smooth side (often

darker) is the top (dorsal — dorso = the back) and the

segmented side (often lighter) is the bottom (ventral).

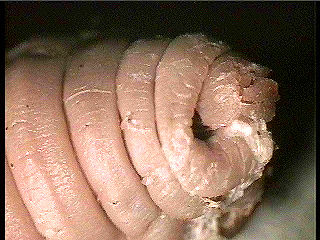

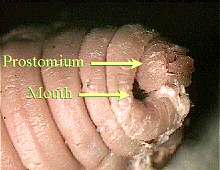

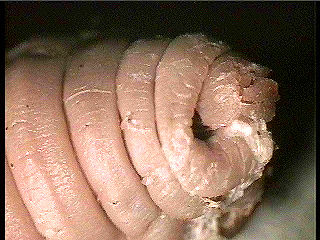

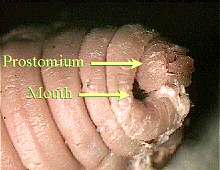

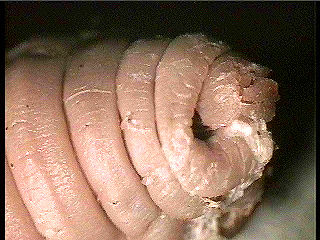

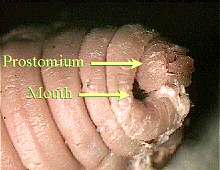

External View, Mouth

Labeled Mouth

- On the very anterior tip of the worm

is a projection called the prostomium (pro = before, in front

of; stoma = mouth). The mouth lies ventrally between this and

the first segment. Count the number of segments between the front of the

worm and the front edge of the clitellum, as well as the number of segments

included in the clitellum.

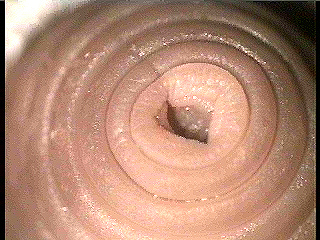

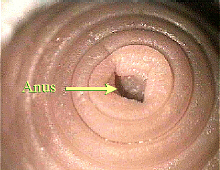

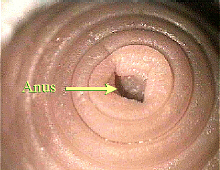

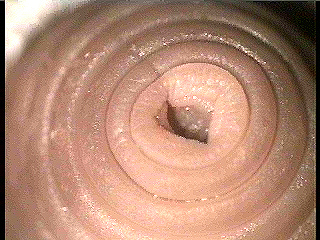

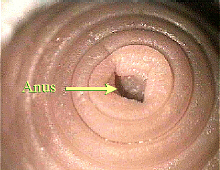

External View, Anus

Labeled Anus

- On the posterior (the rear —

post = behind, after) end, note the slit-like anus in the last

segment.

External View, Genital Openings

Labeled External Genitalia

- On the ventral (bottom)

surface of segment 15, note the pair of (larger) openings of the vasa

deferentia. On the ventral surface of segment 14, you can see the

(smaller) openings of the oviducts (vasa = a vessel, duct;

deferens = to carry away; ovi = egg).

Internal Anatomy:

- On the dorsal surface of the

earthworm, beginning at the clitellum, cut a slit posteriorly (toward the

rear) for about 25 segments. You must cut very shallowly to avoid

cutting the internal organs. Turn the scissors and cut anteriorly to the

prostomium, again, being careful not to cut the internal organs.

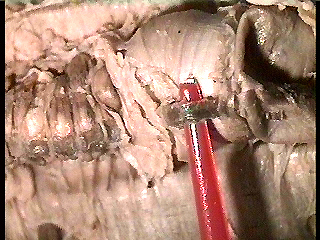

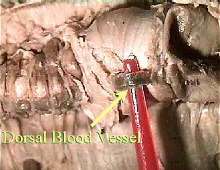

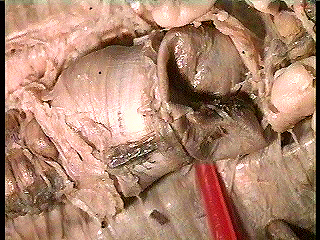

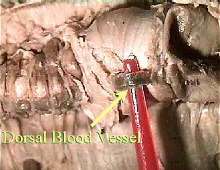

Internal View, Dorsal Blood Vessel

Labeled Dorsal Blood Vessel

- Pin the worm to the tray near the

anterior and posterior ends and every five segments (5, 10, 15, etc.) along

the body. You may have to carefully remove/cut the septa

(septum = a fence) separating the segments to open up the body wall.

The dorsal blood vessel and digestive tract should be exposed

at this point.

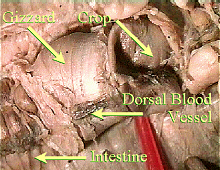

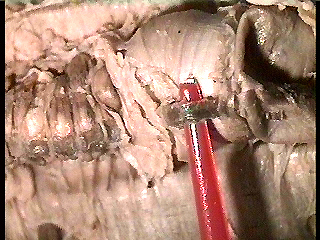

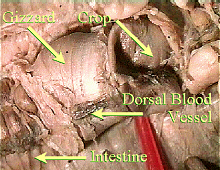

Internal View, Crop and Gizzard

Labeled Crop and Gizzard

- Examine the digestive tract.

From the mouth back, locate the pharynx, esophagus

(eso = within, inward; phago = to eat), crop,

gizzard, and intestine. Refer to these photos, and the

large earthworm model.

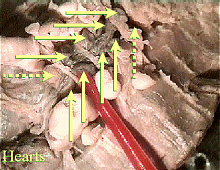

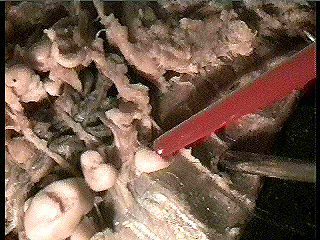

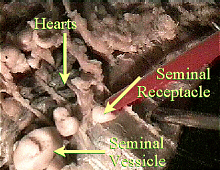

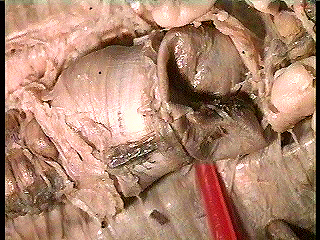

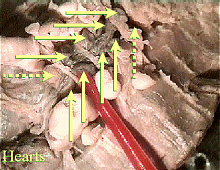

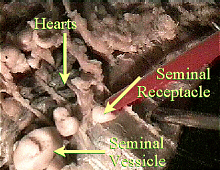

Internal View, Five Pairs of Hearts

Labeled Hearts

- Examine the circulatory system.

Locate the dorsal blood vessel, smaller segmental vessels coming

from it, 5 pairs of hearts in segments 7-10 (count from the placement

of the pins), ventral blood vessel (you may have to carefully snip a

piece of intestine and hold it up to see this).

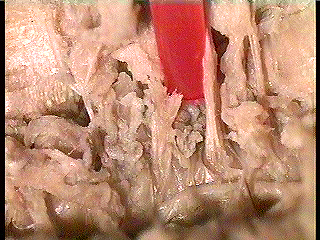

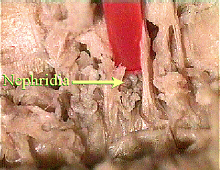

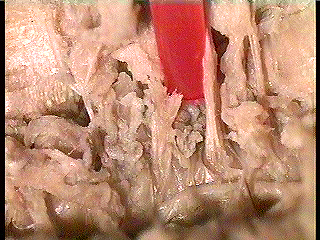

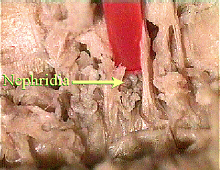

Internal View, Nephridia

Labeled Nephridia

- To the sides/under the digestive

tract are the paired nephridia (nephr = kidney), which may be

too small to see well with the unaided eye.

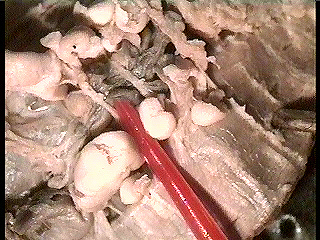

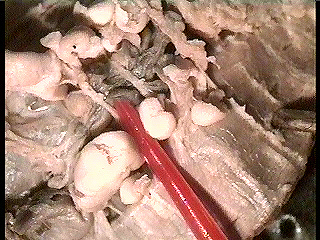

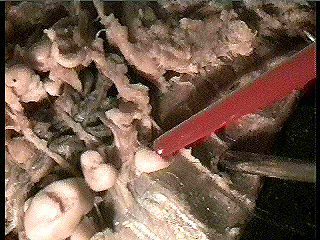

Internal View, Seminal Vesicles and Receptacles

Labeled Seminal Vesicles/Receptacles

- The reproductive systems are

located under the digestive tract in approximately segments 10-15.

Earthworms are hermaphroditic (Hermes = messenger god —

Mercury; Aphrodite = goddess of love — Venus), that is, they have

both sexes and when they mate, they fertilize each other. Seminal

vesicles (male organs) are large, floppy, whitish structures in segments

9-13. The tubes from them to segment 15 are the vasa deferentia.

Attached to the anterior septum of segment 13 is a pair of whitish,

grape-clustered ovaries (female organs) which are very difficult to

see. The seminal receptacles, sperm-storage areas within the female

reproductive tract, are smaller, whitish organs near the seminal vesicles.

Oviducts start at the ovaries, go past the seminal receptacles, then

to segment 14, from which they open to the outside.

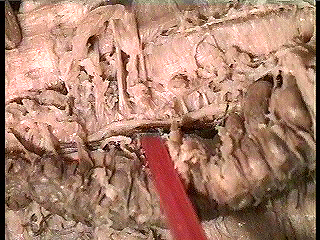

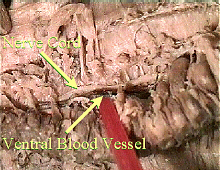

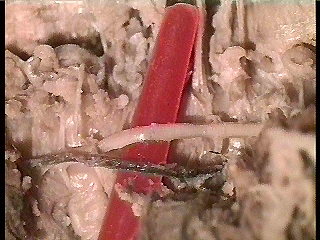

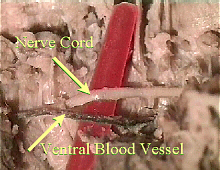

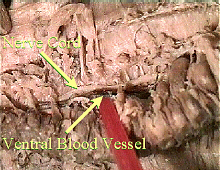

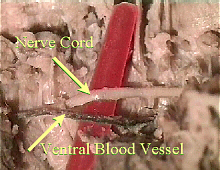

External View, Ventral Nerve Cord and Ventral Blood Vessel

Labeled Nerve Cord & Blood Vessel

- Note the ventral nerve cord

with segmental ganglia (ganglion = a knot on a string). If

you lift a section of the digestive tract/blood vessels, the nerve cord

should be seen lying on the ventral surface of the body cavity.

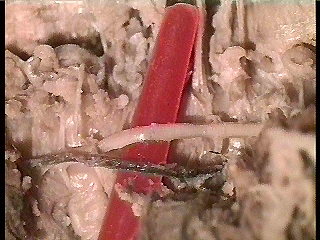

Internal View, Ventral Nerve Cord and Blood Vessel

Labeled Nerve Cord & Blood Vessel

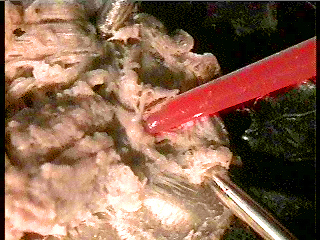

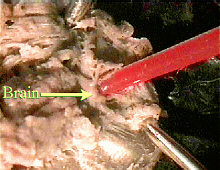

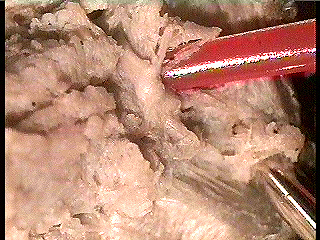

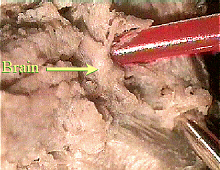

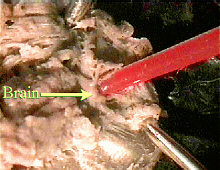

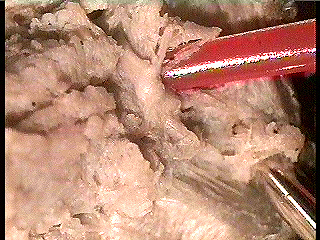

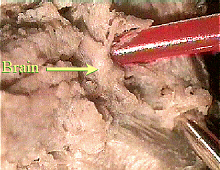

Internal View, Brain

Labeled Brain

- If you look carefully at the nerve

cord, you may be able to see that it is actually two, paired cords. As you

proceed anteriorly, the “last” segmental ganglion (the subpharyngeal

ganglion) will be found in segment #4. From there, the two “halves” of

the nerve cord (the circumpharyngeal connectives) split and go around

either side of the pharynx. Above the pharynx, they come together, again,

to form the suprapharyngeal ganglion, also called the brain.

To aid you in finding your worm’s brain, Dr. Fankhauser has described the

worm brain as looking like the top half of a woman’s bikini bathing suit.

Internal View, Brain

Labeled Brain

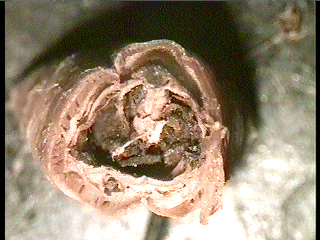

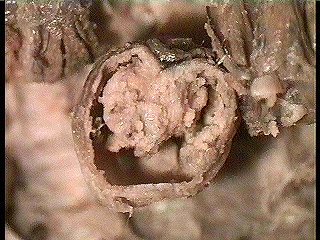

Cross-Section of Earthworm Segment

Cut a thin cross-section through your worm’s intestinal area

and view it with a dissecting scope. Also, view the prepared slide of

an earthworm cross section (Carolina #Z1250), and examine the large model

worm.

Cross Section, Whole Worm

Labeled Worm Cross Section

- Note/draw the layers in the body wall

from the outside in: cuticle secreted by the epidermis,

epidermis (epi = upon, over, beside) — made of ectoderm

tissue, then circular muscle layer, longitudinal muscle layer,

and parietal peritoneum (pariet = a wall; peri = around;

ton = something stretched; -eum = a place where;

peritoneum = the membrane around the intestines) — all mesoderm

tissues (meso = middle). Note the four areas where the setae are

located, although you may not see the actual setae

on your slide.

Intestinal Area, x.s., Actual View

Intestinal Area, x.s., Microscopic View

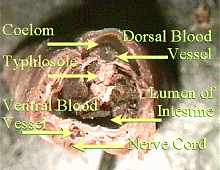

- Note the coelom (coelo

= hollow), the body cavity. Often there is a tangled network visible within

the coelom which is part of the nephridia, the excretory organs.

Each nephridium opens to the outside via a nephridiopore (which may

not be visible on your slide).

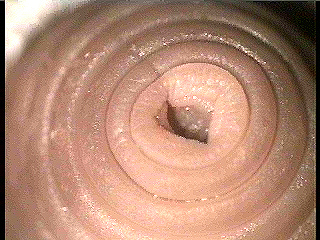

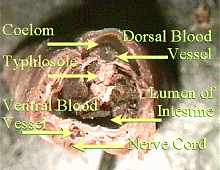

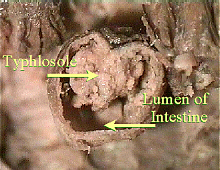

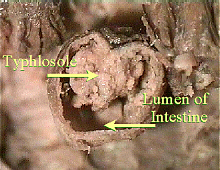

Cross Section, Central Tube

Labeled Intestinal Cross Section

- Examine the central tube. Note that

its upper (dorsal) surface is folded into the digestive tract. This portion

is called the typhlosole (typhlo = blind; solen =

channel, pipe), and helps to increase the surface area of the digestive

tract. (Note: if you carefully open a length of your worm’s intestine

(and clean out the soil/food contained therein), you may be able to see the

typhlosole running the length of the dorsal surface and somewhat resembling

a tightly-coiled spring.) The layers of the central tube, from outside in,

are the chloragen cells,

then thin muscular layers (both mesoderm), then the gastric

epithelium (gastro = stomach, theli = nipple), which is

endoderm tissue, as the lining of the digestive tract. The space

within the digestive tract is known as the lumen. Dorsally and

ventrally of the digestive tract run the dorsal and ventral blood

vessels. Ventrally, in the coelom, there is a nerve cord that

runs the length of the body.

Other Things to Include in Your Notebook

Make sure you have all of the following in your lab notebook:

- all handout pages (in separate protocol book)

- all notes you take as you read through the Web page and/or

during the introductory mini-lecture

- all notes and data you gather as you perform the lab

- labeled drawings (yours!) of

- overall external anatomy

- external view of anterior end

- external view of posterior end

- external, ventral view of segments 14-15

- external arrangement of setae

- overall internal anatomy (dorsal view)

- “close-up” of any internal organs of special interest,

such as the “brain”

- cross-section of intestinal segment

- answers to all discussion questions, a summary/conclusion in your

own words, and any suggestions you may have

- any returned, graded pop quiz

Copyright © 1999 by J. Stein Carter. All rights reserved.

Based on printed protocol, background, and other information

Copyright © 1989, Labeled photos Copyright © 2005 J. L. Stein Carter

Chickadee photograph Copyright © by David B. Fankhauser

This page has been accessed  times since 8 Apr 2006.

times since 8 Apr 2006.