Bacterial Shapes Most bacteria are one of three shapes (although there are a few other possibilities):

“Bacteria” is a plural word. The singular for this word is “bacterium” (bacter = rod, staff). Bacteria are prokaryotes (Kingdom Monera), which means that they have no true nucleus. They do have one chromosome of double-stranded DNA in a ring. They reproduce by binary fission. Most bacteria lack or have very few internal membranes, which means that they don’t have some kinds of organelles (like mitochondria or chloroplasts). Most bacteria are benign (benign = good, friendly, kind) or beneficial, and only a few are “bad guys” or pathogens.

Kingdom Monera is a very diverse group. There are some bacteria relatives that can do photosynthesis — they don’t have chloroplasts, but their chlorophyll and other needed chemicals are built into their cell membranes. These organisms are called Cyanobacteria (cyano = blue, dark blue) or bluegreen algae, although they’re not really algae (real algae are in Kingdom Protista). Like us, some kinds of bacteria need and do best in O2, while others are poisoned/killed by it.

Bacterial Shapes

Most bacteria are one of three shapes (although there are a few other

possibilities):

While many bacteria live singly, others are found in aggregates or clusters. These aggregates are named based on the arrangement of the bacterial cells of which they are composed. Using cocci as an example:

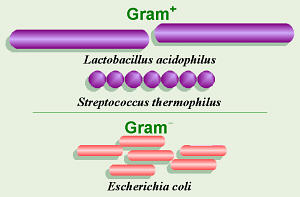

Gram Positive and Gram Negative Bacteria

Most bacteria secrete a covering for themselves which we call a cell

wall, However, bacterial cell walls are a totally different thing than

the cell walls we talk about plants having. Bacterial cell walls do

NOT contain cellulose like plant cell walls do. Bacterial cell walls

are made mostly of a chemical called peptidoglycan (made of

polypeptides bonded to modified sugars), but the amount and location of the

peptidoglycan are different in the two possible types of cell walls,

depending on the species of bacterium. Some antibiotics, like penicillin,

inhibit the formation of the chemical cross linkages needed to make

peptidoglycan. These antibiotics don’t outright kill the bacteria, but just

stop them from being able to make more cell wall so they can grow. That’s

why antibiotics must typically be taken for ten days until the bacteria,

unable to grow, die of “old age”. If a person stops taking the antibiotic

sooner, any living bacteria could start making peptidoglycan, grow, and

reproduce.

However, because one of the two possible types of bacterial cell walls has more peptidoglycan than the other, antibiotics like penicillin are more effective against bacteria with that type of cell wall and less effective against bacteria with less peptidoglycan in their cell walls. Thus it is important, before beginning antibiotic treatment, to determine with which of the two types of bacteria one is dealing. Dr. Hans Christian Gram, a Danish physician, invented a staining process to tell these two types of bacteria apart, and in his honor, this process is called Gram stain. In this process, the amount of peptidoglycan in the cell walls of the bacteria under study will determine how those bacteria absorb the dyes with which they are stained, thus bacterial cells can be Gram+ or Gram –. Gram+ bacteria have simpler cell walls with lots of peptidoglycan, and stain a dark purple color. Gram– bacteria have more complex cell walls with less peptidoglycan, thus absorb less of the purple dye used and stain a pinkish color instead. Also, Gram– bacteria often incorporate toxic chemicals into their cell walls, thus tend to cause worse reactions in our bodies. Because Gram– bacteria have less peptidoglycan, antibiotics like penicillin are less effective against them. As we have discussed before, taking antibiotics that don’t work can be bad for you, thus a good doctor should always have a culture done before prescribing antibiotics to make sure the person is getting something that will help.

Within the past several years, I have had several pet birds who have had digestive system or other infections. When I’ve taken them to the vet for treatment, one of the very first things she has always done is to take a sample/swab, prepare a microscope slide, Gram-stain the slide, then count and calculate the percentage of Gram+ and Gram– bacteria on the slide. Birds’ systems are supposed to contain close to 100% Gram+ bacteria, so finding a high percentage of Gram– bacteria is not good! In one case, I subsequently smeared some fecal material from a sick “girl” on an agar plate containing a special kind of medium called “EMB agar,” and after incubation, discovered that way that the “bad guys” in her system were all E. coli, a species that normally lives in the gut of mammals and shouldn’t be in birds. The thing is, though, if the vet can keep Gram stain dyes, microscope slides, and a microscope in the office and routinely do Gram stains, there’s no reason people-doctors can’t do the same.

One “famous” person who worked with bacteria was Dr. Robert Koch, a German physician. He is famous for several discoveries related to bacteria: