Lipids and Emulsifying Agents: Mayonnaise

It’s All About Eggs

This egg was hand-painted by Barbara Muth, a friend who is a very talented egg painter. In addition to painting eggs or decorating them in other elaborate ways, we use eggs for many purposes, including eating them, cooking with them in various recipes, using them in scientific research, using them to make a durable paint, and using them in magic tricks. However, think for a few minutes about the “real” purpose for which an egg was designed.

Eggs and Chickens

One way in which hens and human females are similar is that both ovulate on

a regular basis, even if the eggs which are produced aren’t fertilized. As

you hopefully know, human females ovulate about once every 28 to 29 days,

and the vast majority of those eggs never get fertilized, but the woman has

her period, instead. Similarly, hens ovulate about every 1½ to 2 days. One

difference is that after ovulation, a hen’s reproductive system will

subsequently add a yolk and albumen to the actual egg, then coat the whole

thing with an eggshell, prior to releasing it from her body. Those

unfertilized eggs are packaged into cartons and sold in our grocery stores.

One way in which hens and human females are similar is that both ovulate on

a regular basis, even if the eggs which are produced aren’t fertilized. As

you hopefully know, human females ovulate about once every 28 to 29 days,

and the vast majority of those eggs never get fertilized, but the woman has

her period, instead. Similarly, hens ovulate about every 1½ to 2 days. One

difference is that after ovulation, a hen’s reproductive system will

subsequently add a yolk and albumen to the actual egg, then coat the whole

thing with an eggshell, prior to releasing it from her body. Those

unfertilized eggs are packaged into cartons and sold in our grocery stores.

(This is Morwen, a little, 3-lb, Cochin Banty

fluff-ball.)

In humans, if a couple has intercourse at just the right time so that his

sperm can swim up the woman’s reproductive tract and be present when she

ovulates, there’s a good chance she’ll become pregnant. Similarly, if there

are roosters around, a hen and a rooster may mate, and his sperm must swim

up her reproductive tract to fertilize the actual egg cell before the

hen’s body adds the yolk, egg white, and shell.

In humans, if a couple has intercourse at just the right time so that his

sperm can swim up the woman’s reproductive tract and be present when she

ovulates, there’s a good chance she’ll become pregnant. Similarly, if there

are roosters around, a hen and a rooster may mate, and his sperm must swim

up her reproductive tract to fertilize the actual egg cell before the

hen’s body adds the yolk, egg white, and shell.

(This guy is out at Dr. Fankhauser’s farm.)

One difference between chickens and humans is that, while a human zygote

(the cell that results from the union of the egg and sperm) immediately begins

to develop, chicken zygotes can wait up to a week or so to begin development

and will only begin development if kept at a warm-enough temperature. That

way, a hen has time to lay several eggs in her nest, yet all the chicks will

hatch at the same time. After laying a number of eggs, a hen may “go broody”

and brood her clutch of eggs (incubate them, sit on them to keep them

warm).

One difference between chickens and humans is that, while a human zygote

(the cell that results from the union of the egg and sperm) immediately begins

to develop, chicken zygotes can wait up to a week or so to begin development

and will only begin development if kept at a warm-enough temperature. That

way, a hen has time to lay several eggs in her nest, yet all the chicks will

hatch at the same time. After laying a number of eggs, a hen may “go broody”

and brood her clutch of eggs (incubate them, sit on them to keep them

warm).

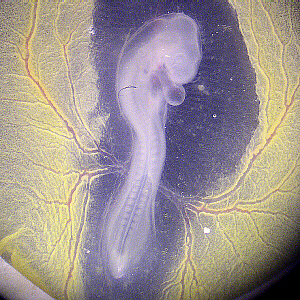

The warmth provided by her body allows the zygotes to develop into chicks.

Regardless of the order in which they were laid, three days after she begins

to incubate them, the embryos in the eggs will all look like the 72-hr.

embryo in this photograph by Dr. Fankhauser. To

insure that the embryos are kept warm enough to develop properly,

during the time they are developing, the hen sits on her eggs continuously,

only leaving her nest once a day for just long enough to defecate and eat

a quick meal.

The warmth provided by her body allows the zygotes to develop into chicks.

Regardless of the order in which they were laid, three days after she begins

to incubate them, the embryos in the eggs will all look like the 72-hr.

embryo in this photograph by Dr. Fankhauser. To

insure that the embryos are kept warm enough to develop properly,

during the time they are developing, the hen sits on her eggs continuously,

only leaving her nest once a day for just long enough to defecate and eat

a quick meal.

Then, 21 days later, her eggs hatch, and she has a family of fuzzy chicks

to raise. They still need to be kept warm for a few more weeks, and she

has to teach them what’s good to eat and put up with them jumping up on

her back to play.

Then, 21 days later, her eggs hatch, and she has a family of fuzzy chicks

to raise. They still need to be kept warm for a few more weeks, and she

has to teach them what’s good to eat and put up with them jumping up on

her back to play.

(Morwen went broody and was given some

“adopted” eggs from Dr. Fankhauser’s farm. Here she is with two-day-old

Nim.)

What’s in an Egg?

An egg has to provide protection, food, and air for the developing embryo for the whole 21 days. Think about how much space would be needed to store all the food you eat in 21 days! All the vitamins, protein, and energy the embryo chick needs to grow must be packaged into the egg — that’s the growing embryo’s only source of food for that whole time. As mentioned above, the hen’s reproductive tract adds three main things to the egg before it is laid.

One note here about “egg safety:” because egg shells are porous, there is a possibility that washing eggs may actually give bacteria a route by which to enter the egg. If eggs are washed just before use, this would not be a problem because the number of bacteria would be negligible. However, if eggs are washed just after the hen lays them (as is routinely done in “egg factories”), then packaged into egg cartons, then sit for a while until shipped to a grocery store, then sit for a while at the grocery store until purchased, then sit for a while in your refrigerator until used, that may give any bacteria that did enter the egg a chance to grow and multiply, so by the time the eggs are used, the bacterial count may be significantly higher, perhaps enough to make someone sick. To prevent bacterial growth in eggs, if washing is even needed (which it usually is not), they should not be washed until just before use.

How Does It All Fit in There?

So how do you cram 21-days’-worth of nutrition into one egg yolk? The amount of vitamins and minerals needed by a small embryo growing into a small chick is small enough to fit without too much of a problem, and the hen’s body manages to cram sufficient protein into the yolk, too. (Note, by the way, that the nutritional value of an egg is dependent on the hen being well-fed. Hens who live in “egg factories” and only get human-made “laying mix” to eat typically lay eggs with very pale yellow yolks, while free-range, farm hens who get to eat dark-green leafy vegetation, food scraps, etc., typically lay eggs with dark orangish yolks due to the presence of a lot more vitamins.) A bigger challenge is to fit 21-days’-worth of energy (Calories) into as small of a space as possible.

The solution to that problem is rather interesting. You

may recall hearing that 1 g of protein or 1 g of carbohydrate stores/provides

4 KCal of energy, while 1 g of lipid (fat, oil) stores/provides 9 KCal of

energy. That means that by providing the growing chick embryo with energy

stored in lipids (fats) rather than carbohydrates (sugar), the

same amount of energy will require only 44% as much storage space. For

example, an average egg weighs about 50 g and contains about 5 g of lipids,

so that’s equivalent to 45 KCal of energy. If that 45 KCal of energy would

be stored as carbohydrate, instead, that would weigh a little over 11 g.

That means the overall weight of the egg would have to increase by a little

over 6 g, or 12.5% of the original weight of the egg.

However, there is one small detail to be worked out when storing energy as

lipids. That

50-g egg contains about 38 g of water. Granted, a lot of that water is out

in the albumen (egg white), but there’s a lot in the yolk, too. As you may

recall, and as shown in this photo, oil and water do not mix. This little

glass contains vinegar (a water-based solution), which is the brownish liquid

on the bottom, and salad oil, which is the pale-yellow liquid on the top.

Even if we’d shake up this glass, the vinegar and oil would just separate,

again. Thus it won’t work to have an egg yolk that contains just water and

lipids, because the same separation would occur there. An egg yolk needs to

also contain some substance that would enable the oil and water to stay mixed

together.

However, there is one small detail to be worked out when storing energy as

lipids. That

50-g egg contains about 38 g of water. Granted, a lot of that water is out

in the albumen (egg white), but there’s a lot in the yolk, too. As you may

recall, and as shown in this photo, oil and water do not mix. This little

glass contains vinegar (a water-based solution), which is the brownish liquid

on the bottom, and salad oil, which is the pale-yellow liquid on the top.

Even if we’d shake up this glass, the vinegar and oil would just separate,

again. Thus it won’t work to have an egg yolk that contains just water and

lipids, because the same separation would occur there. An egg yolk needs to

also contain some substance that would enable the oil and water to stay mixed

together.

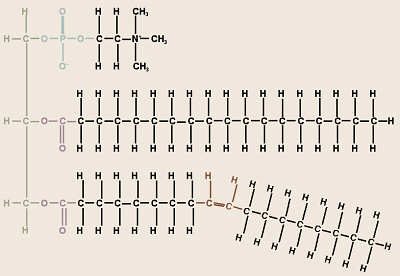

The solution is to include lecithin, a type of phospholipid.

Note that this molecule contains a glycerol backbone that is bonded to two

fatty acid chains (from the bottom two carbons) and to a phosphate group

(from the top carbon) that is also bonded on to “something else.” The long,

fatty acid chains are hydrophobic, and as such are soluble in lipids

such as fats, oils, cholesterol, etc. The phosphate group is ionic, and has

a lot of polar oxygen atoms in it, so that “end” of the phospholipid

molecule is hydrophilic (water-soluble). Because of that,

phospholipids, such as lecithin, are emulsifying agents, substances

which are soluble in both oil and water, thereby enabling those two

substances to mix together. That forms an emulsion in which the fat

is divided into tiny droplets and dispersed among the water-based solution.

The solution is to include lecithin, a type of phospholipid.

Note that this molecule contains a glycerol backbone that is bonded to two

fatty acid chains (from the bottom two carbons) and to a phosphate group

(from the top carbon) that is also bonded on to “something else.” The long,

fatty acid chains are hydrophobic, and as such are soluble in lipids

such as fats, oils, cholesterol, etc. The phosphate group is ionic, and has

a lot of polar oxygen atoms in it, so that “end” of the phospholipid

molecule is hydrophilic (water-soluble). Because of that,

phospholipids, such as lecithin, are emulsifying agents, substances

which are soluble in both oil and water, thereby enabling those two

substances to mix together. That forms an emulsion in which the fat

is divided into tiny droplets and dispersed among the water-based solution.

Soap is another example of an emulsifying agent: it allows oily “dirt” to mix with water so it can be washed out of one’s clothing or off one’s dishes. Milk and blood are other examples of emulsions.

Mayonnaise

The lecithin in egg yolk can emulsify a lot more than just what s in the

yolk, and that’s the basis of the emulsion known as mayonnaise.

In mayonnaise, an egg yolk is used to blend together an acidic, watery

substance and an oily substance. There are several conjectures as to the

origin of mayonnaise, but the most popular story is that it originated in

Mahón in Minorca, Spain, and from there was introduced into France, possibly

with the original French name of “mahonnaise” (meaning of/from Mahón,

in the style of Mahón). From what I’ve read, in the original Spanish and

French versions, olive oil is always used, and either lemon juice or vinegar

may be used as the acid. Also, it sounds like while the original Spanish

version never contains powdered mustard, in the traditional French version,

mustard is always added as a seasoning.

The lecithin in egg yolk can emulsify a lot more than just what s in the

yolk, and that’s the basis of the emulsion known as mayonnaise.

In mayonnaise, an egg yolk is used to blend together an acidic, watery

substance and an oily substance. There are several conjectures as to the

origin of mayonnaise, but the most popular story is that it originated in

Mahón in Minorca, Spain, and from there was introduced into France, possibly

with the original French name of “mahonnaise” (meaning of/from Mahón,

in the style of Mahón). From what I’ve read, in the original Spanish and

French versions, olive oil is always used, and either lemon juice or vinegar

may be used as the acid. Also, it sounds like while the original Spanish

version never contains powdered mustard, in the traditional French version,

mustard is always added as a seasoning.

Now, the use of mayonnaise has

spread worldwide, and there are many national and “gourmet” variations on

the type of acid (lemon juice or any of a wide variety of vinegars), type

of oil (olive oil, cheap “salad” oil, or a variety of other oils), and types

of other spices (rosemary, basil, hot peppers, etc.) which may be added.

There is also a wide variety of other additives, from the sugar and starchy

fillers used in commercial mayonnaise (especially “light” mayonnaise) to

tomato-based products (tomato paste, ketchup) to pickle relish to blue

cheese, etc., which may be added. When mayonnaise is mixed by hand with a

whisk, typically

only the egg yolk is used, but when mixed in a blender, often the whole egg

is added. Some kinds of egg-free “mayonnaise” use lecithin from soy beans.

While cheap, store-bought mayonnaise may contain things like distilled white

“vinegar” (chemically-synthesized acetic acid diluted to 5%), low-grade,

generic “salad” oil, starch and other fillers to mimic the consistency of

mayonnaise, and sugar, on the other hand, the taste and quality of home-made

mayonnaise can be varied greatly through the creative use of lemon juice or

different vinegars (balsamic, wine, malt, cider, rice, etc.), different oils

(olive, hazlenut, walnut, avocado, corn, etc.), and different herbs and

spices (mustard, chili powder, curry, rosemary, garlic, etc.). Many people

who take the time to make their own mayonnaise will use high-quality, organic,

cold-pressed oils, and if using olive oil, will also choose extra-virgin (the

first, highest-quality pressing from the olives). If using lemon juice, they

will squeeze their own from fresh, organic lemons, or if using vinegar, will

use an organic vinegar, perhaps a balsamic or wine vinegar. They may also

seek out a source for fresh-from-the-farm, organic eggs from free-range

chickens, or if space allows, raise their own chickens and use their own

eggs. Use of a spice grinder to grind whole spices immediately before

adding them to the mayonnaise can greatly enhance the flavor as compared to

using purchased, pre-ground spices from which the flavor has had time to

“evaporate.”

Recipe for “Generic” Mayonnaise

Other Things to Include in Your Notebook

Make sure you have all of the following in your lab notebook:

Make sure you have all of the following in your lab notebook: